Uninvent helps startup founders with the most important factor in their success: their team. We help founders manage their own motivation, productivity, health, and relationships with co-founders. We’ll discuss hiring and managing great people, building a strong culture, and keeping people aligned and working on the right things. See the series overview in Welcome to Uninvent.

“In effect, there are two different ways to run a company: founder mode and manager mode. Till now most people even in Silicon Valley have implicitly assumed that scaling a startup meant switching to manager mode. But we can infer the existence of another mode from the dismay of founders who've tried it, and the success of their attempts to escape from it.”

— Paul Graham, Founder Mode1

“God is in the details. But I am not a creative person. I can’t draw, I can’t sketch, I can’t make anything. I just have to make sure things are being done right.”

— Anna Wintour

“It is the responsibility of leadership to work intelligently with what is given and not waste time fantasizing about a world of flawless people and perfect choices.”

— Marcus Aurelias

Lean in or sit back?

Your startup grew from 20 to 25 people this month. You don’t know if that qualifies you as a “Blitzscaler”2, but you feel great about the new talent, especially your new Head of Sales, Agnes, and your new Head of Product, Pablo.

The week they joined, you spent a few hours offloading responsibilities to them. You walked Agnes through recent deals you won and lost, your sales playbook, and your best customer references. You trained Pablo on your product strategy and roadmap and your development process. You finished the week with a company happy hour to welcome them then spent the subway ride home gleefully deleting meetings from your calendar that you handed off. You fell asleep to dreams of hyperscaling.

It’s a month later, and in this morning’s leadership meeting, you are blown away by Agnes’ update. She flipped a set of dormant leads into active opportunities on the brink of closing. She’s made several upgrades to your sales playbook. She has a pipeline of new reps eager to join. You think, “This scale thing is easy!” and mentally pat yourself on the back.

Your love fest with your back stops at Pablo’s update. He shares some new projects he’s launching, and it’s feature salad. None of it connects with your startup’s strategy or goals or solves customer problems. You have an awkward discussion ahead of you where you’ll have to ask him to change the roadmap and pause the projects he just launched. You imagine his pushback: “Why did you hire me if you don’t trust me?”

You leave the meeting confused. You know that scaling your startup means hiring good people and delegating, but now you’ve been both rewarded and punished for doing just that. Don’t be too surprised, though. All founders face this dilemma, but you're more likely to succeed if you Activate Founder Mode.

Micro-manage, macro-manage?

Conventional management wisdom is “hire great people and get out of the way.” That would seem to make sense for a growing startup, given how much work there is and how much talent you need to do it. Plenty of startups fail because their founders don’t learn to hire great people, train them, and trust them to take on important work.

But anyone who has worked at an early-stage startup knows this is incomplete advice. Founders struggle with which work to delegate and which to do themselves. They agonize about overruling decisions made by their team versus letting them stand. They debate which parts of their business they should go deep into and which areas to hand off. In my 30-year startup career, not a week has gone by that my teams didn’t struggle with these questions. It’s the core dilemma of managing at a startup.

Paul Graham’s Founder Mode essay, based on a talk by Brian Chesky, resonated with founders like me because it pinpointed that tension and gave it a name. We are told we should hire good people and delegate, but we see that fail constantly. We hate being micromanaged, but are tempted to micromanage others. We want to build our startup into a big company, but we know we can’t manage it like it already is.

Unpacking these dilemmas requires remembering why a startup isn’t just a smaller version of a big company3. A startup is growing like crazy, changes every month, and is always adding new people. It has to constantly learn as competitors and incumbents respond. It has little room for error and can’t afford to waste much time or money. Most of all, it has to be as innovative at 100 employees as it was at five.

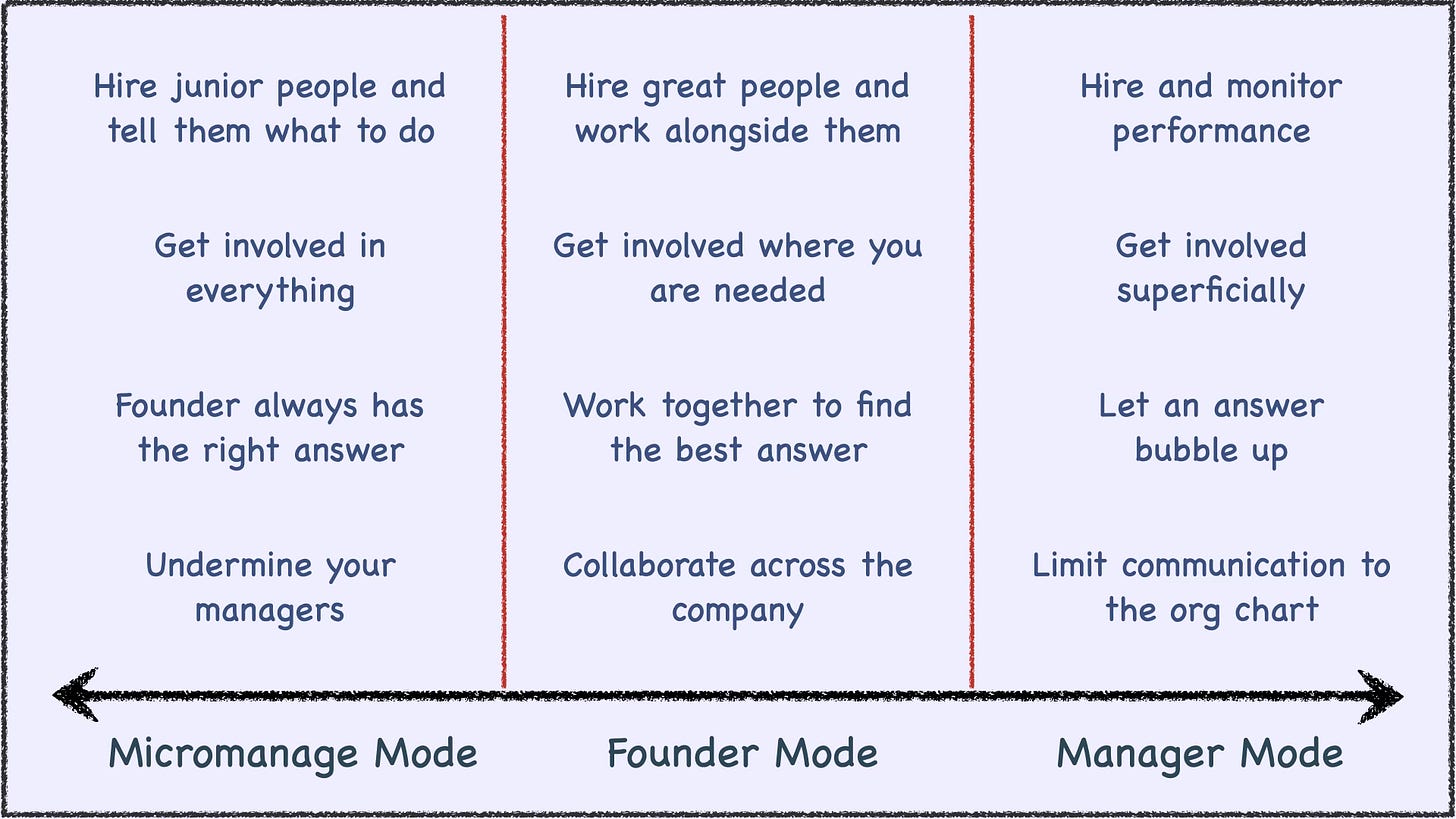

Hiring people, handing them the work, and hoping for the best rarely solves these challenges, but micromanaging every person and project won’t either. As is usually the case, it’s not a binary choice.

Paul Graham doesn’t go deep on Founder Mode, but I can weigh in with my own definition. Founder Mode means learning where you should go deep and where you should sit back. It’s spending time with the right people and projects and letting others run on their own. It’s learning how to manage people and projects tightly but in a way that builds trust instead of eroding it. It’s accepting the risk of failure but not accepting sloppiness and low quality.

Founder Mode means learning to:

Pick your spots

Most of us want to be fair and treat people equally. If we have five direct reports, we assume we should manage them the same way, spend the same amount of time, and tell them their work is equally important.

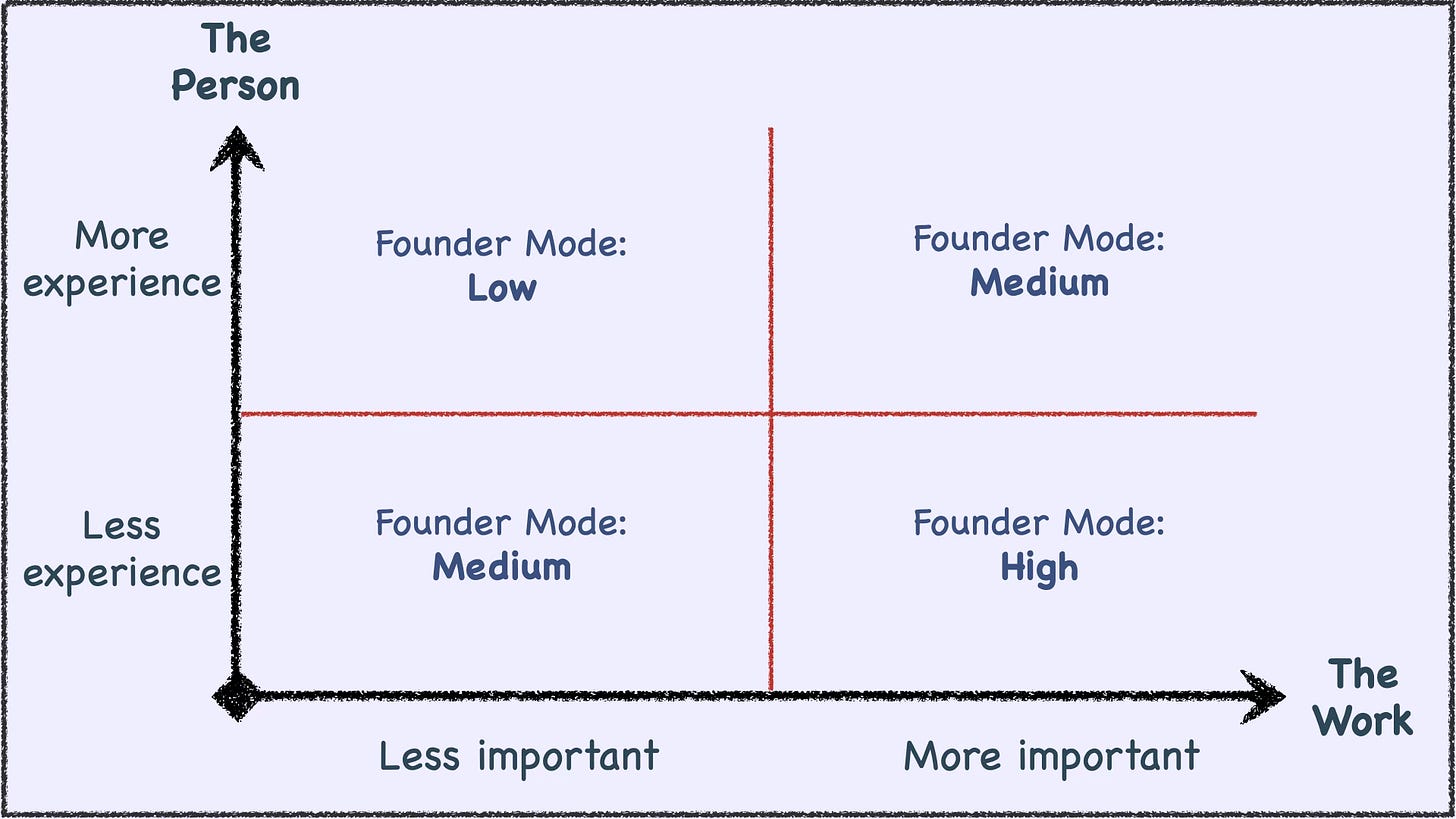

We shouldn’t. People aren’t all the same, and the work isn’t all the same. You should spend more time and be more hands-on with the most critical projects and the least experienced people:4

If you are running out of money in three months, devote time to raising the round and work closely with the people who will help get that done, like your finance team. Don’t hesitate to tell other teams that their work is less important and that they’ll get less of your time, at least for now. You have to prioritize. Launching a new product is more important than optimizing your tech support. Designing your brand is more important than designing your office.

Your people are different and need different amounts of time and focus. Some will be new and be ramping up, where others will be more established. Some will have proven their excellence, and the jury will still be out on others who might not make it.

Find out where you are needed, put your time and energy there, and be willing to roll up your sleeves and go deep.

Build a Founder Mode team

Most startup management challenges have less to do with how you manage your team and more to do with who you hired in the first place, especially for executive hires, many of whom don’t work out and either quit or are asked to leave. Many of the startups I work with at Point Nine and elsewhere assume that up to half of their executive hires will fail, with many of them failing because they can’t work in Founder Mode.

A common failure path is to hire an executive from a larger company who can't adjust to a startup. The executive builds a silo and runs their team with little input from you or from others. They aren’t hands-on enough to know if the work is any good, and their solution to problems is to ask for more budget to hire even more people.

Hire leaders who know their job is to get input from you and others and be willing to put their work up for scrutiny. Hire managers who are able and willing to activate Founder Mode themselves. They do exist; the best startups are full of them. You don’t want a team of managers who are too defensive to get feedback and too timid to give it.

And stay open to internal promotions, who often outperform outside hires even when they have far less experience on paper. They grew up in your company, are hands-on enough to contribute to the work, and are used to the discussion and debate that characterize a startup.

Front-load new hire training

Many founders, like the ones from our vignette, assume they should hire a senior person, spend a few hours training them, and then turn them loose, assuming anyone worth hiring can take over the job from there. This sometimes works, but it’s better to assume you have to make a big upfront investment in them.

If you hand off too quickly, you’ll get Pablo from our vignette, where a few weeks after the new executive starts, something isn’t quite right. Little work is getting done, and what does get done is low quality. Their proposed new hires make you scratch your head. They don’t know the details of the work. You now have to spend time and energy unwinding some decisions, and the team has lost faith in your new hire and in you for hiring them.

A better plan is to front-load the time you spend with a new hire and devote several hours a week for several weeks. Walk them through how you do things at your company. Shadow them on their first few projects. Sit in some meetings with them. Brainstorm solutions to problems.

They will get up to speed more quickly, and you’ll learn how to work together. You’ll also both discover if they are a fit for your company earlier. If they aren’t going to work out, both of you are far better off pulling the ripcord early.

Let the work guide you

Your startup has to deliver excellent work and deliver it quickly. As a founder, you are responsible for every piece of work that comes out of your company, whether you created it or someone you hired did. If you hire someone, delegate the work to them, and the work isn’t great, then you hired the wrong person, delegated too early, or didn’t delegate the right way.

Use the work to lead you to where you should spend your time. If the work from one part of your organization is excellent, congratulations. You probably don’t need to spend much time with that team other than checking in regularly and recognizing and rewarding them.

In the areas where the work isn’t excellent, dig in. The people on that team might just need some more coaching and feedback. You might need to step in and help resolve some important decisions. In the worst case, you might have the wrong person running the team, and you have to ask them to leave and bring in someone new. But you can’t just sit back and hope things improve on their own.

Know your own strengths and weaknesses so you know which of your opinions you can be more confident in. But don’t limit yourself too much. Maybe you’ve never run a sales team before and your Head of Sales has, but you do know if you are making your plan or not, and you are perfectly capable of calling a prospect and asking why they didn’t buy or calling a sales rep and asking what help they need. You can also lean on your board and advisors in areas where you are weaker.

Talk to everyone

BigCo managers can get with just interacting with their direct reports and a few peers, which can come from big company politics, where managers want to control the information coming in and out of their team. “Stay off my turf, and I’ll stay off of yours” doesn’t work at a startup, though.

You need to know what’s happening in your own company. Find out how people are feeling and what questions and concerns they have. Test if they understand your strategy and plans. Find out who is performing well and who is struggling.

Have skip-level one-on-ones. Talk to people working on important projects and critical deals. Have ad hoc conversations with whomever you bump into in the elevator or the lunch room. Encourage everyone who works for you to do the same thing.

If a manager at your startup is possessive and wants to “protect” their people from “being distracted” by anyone but them, that’s not a leader you want at your startup.

Be curious, not judgmental

“Good people hate to be micromanaged” is accepted wisdom in modern management, but it has some nuance. When people complain about micromanaging, it’s usually about how that management is delivered. People will always remember how you made them feel, and all that.5

People bristle when feedback seems arbitrary or is delivered disrespectfully. If one of your product managers has interviewed 25 customers and put a hundred hours into designing a new feature, they won’t react well if you fire off a curt midnight Slack message telling them their solution is wrong and you know the right one.

Lead with curiosity instead.6 Ask what assumptions were behind the work. Ask what constraints they were under. Ask what else they considered. You might learn you don’t have all of the background. Maybe they have insight you don’t. They might be operating off of the wrong information or were never trained properly, which is your fault but something you can fix. You might learn that you’re just wrong, which should happen a lot unless you really are better at every job than every person at your startup, in which case you have bigger problems.

You will seldom hear someone complain about micromanagement if you treat them with respect, lead with genuine curiosity, consider the possibility you are wrong, and take the time to collaborate on the best solution.

Bake feedback into your operating system

Manager feedback also gets a bad rap because it’s often delivered reactively and unpredictably. You might have scars from a “Dilbert” manager at a previous job who would show up at a meeting for a project that is halfway done and dump feedback on the team that they are on the wrong track. Everyone gets frustrated, the work needs to be redone, and the team starts to flinch when they see the manager coming.

It’s more productive to bake feedback into the day-to-day cadence of running the company. Use your one-on-ones with your team members to regularly give and get feedback on their work. Schedule regular review meetings for important projects. Establish checkpoints for projects where you and other people will give feedback, and schedule them early enough in the project that work doesn’t have to get thrown out and redone.

You want to be known as a manager who helps teams do excellent work, not one who derails projects. Make the investment up front to make that happen, and tell everyone else you expect them to do the same.

Solve problems once

Sometimes, you’ll see work delivered by your startup that doesn’t meet your high standards. It might be a slideshow that’s ugly and misformatted. It might be a sales rep using out-of-date competitive intelligence. There might be more bugs in your product than you can accept.

When this happens, you get disappointed or angry, especially in moments of weakness when you are already tired or frustrated (which is why you should avoid the midnight Slack). It’s tempting to assume that someone screwed up and that you need to track down the culprit.

But it’s more productive to ask a few questions, find the root cause of problems, and propose more systemic solutions. Instead of getting mad at a sales rep for creating ugly slides, have your design team create a beautiful template and train the whole team on how to use it. If your competitive intelligence is wrong, assign a team to solve it and make sure they know to prioritize it.

Your reaction to all of this might be, “Hmm…Founder Mode doesn’t seem unique to startups. It’s just good management, the kind that big companies need, too. This is true. Although Apple could not have built the iPhone without thousands of talented managers and engineers, it also wouldn’t have built the iPhone if Steve Jobs had told that team, “Go build a phone, and if you need any help, I’ll be in my office.”

Some will argue that only a founder like Jobs can operate in Founder Mode. Others say that anyone with enough fortitude can. It doesn’t matter. The point is that you can. Your startup probably wouldn’t even exist if the legacy incumbents in your market had figured it out. Founder Mode is the only sustainable advantage you have over them, so never give it up.

Paul Graham’s Founder Mode essay made the New York Times and has launched dozens of responses from founders and investors. You are reading one of them.

The excellent Reid Hoffman book Blitzscaling covers what happens if your startup goes into hypergrowth.

Steve Blank might have been the first to say “A startup is not a smaller version of a large company.”

This is partially inspired by Andy Grove’s “Task Relevant Maturity” from his book High Output Management.

Maya Angelou said, “I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” I know Angelou wasn’t a management consultant, but this is excellent advice for managing people in tense situations.