Uninvent helps startup founders with the most important factor in their success: their team. We help founders manage their own motivation, productivity, health, and relationships with co-founders. We’ll discuss hiring and managing a great team, building a great culture, and keeping people aligned and working on the right things. See the series overview in Welcome to Uninvent.

In “Start Where You Are,” we’ll talk about how you can take your focus off of the long list of credentials and experiences that you may lack and focus on the list of everything you do have, which is more than you think.

“Intransigence is my only weapon.”

— Charles de Gaulle

“I have had all of the disadvantages required for success.”

— Larry Ellison

“Doubt can only be removed by action.“

— Ted Lasso

Heart of darkness

You and your co-founder have worked for six months on your startup. You’ve had a few bright days when a prospect got excited about your product prototype, but most days are dark, where the world seems cold and indifferent towards your tiny startup.

You need cheering up, so you meet a friend for a hike after work. As the two of you depart the trailhead and head down a steep trail into a dark and narrow ravine, you find yourself pouring your heart out to her.

You confess your fear that you can’t convert your prospects into paying customers. You think your powers of persuasion pale compared to the great sales reps you’ve worked with. They were fearless in sitting down and negotiating with CIOs and CFOs, but you feel like a little kid sitting at the grownups’ table. You wonder if you should hire a senior sales representative and turn the selling over to them, not that you can afford to hire anyone right now.

Gravity feels like it’s strengthening and starts pulling you down a long flight of wooden stairs, and you admit the next thing keeping you up at night — you don’t know where to find your next set of sales leads. You’ve tapped out your meager professional network and can’t afford to advertise. You used to poke fun at gregarious colleagues with thousands of LinkedIn connections, asking how many could be legit relationships. Now, you’d give anything to have that network to mine.

Trees close in on both sides as the trail narrows into a dark tunnel. You share something you’ve never said out loud: you regret changing your major in college from computer science to philosophy. The founders you know who have raised angel funding have technical degrees. Along with your co-founder and a contractor, you’ve successfully hacked together a demo to show prospects, but you fear investors won’t believe your expertise in Kierkegaard and Schopenhauer will translate to Python coding wizardry.

Your friend cuts you off, and you brace yourself for the tough love surely coming your way. She says you seem haunted by a collection of ghosts: colleagues with the skills you lack, investors who might judge you, and parallel universe versions of yourself who made different life choices. She urges you to embrace who you are instead of focusing on who you aren’t. You thank her for the virtual smackdown and start the climb out of the valley, finally catching a glimpse of the setting sun as the trailhead comes back into view.

You aren’t wrong about the challenges you face, but you can only respond one way, which is to do what every startup founder who came before you did: start where you are.

You’re good enough, you’re smart enough

You’d seem to need an implausibly long list of skills to be a startup founder.

Founders need insight and vision into a market opportunity and the design, technical, and product skills to ship one of the rare products that rises above the noise and separates customers from their money.

Founders need sales and marketing skills to attract prospects and turn them into paying customers. They need customer service skills to keep those customers happy. Finally, they need basic finance, legal, and operations knowledge to keep their startups funded and running smoothly.

They need leadership and communication skills to convince recruits to join a tiny startup with little money and few customers. They must be compelling enough to convince investors to give them their money instead of the thousands of other startups that pitch them every year. They have to console a struggling coworker over a beer one moment and wow a thousand people at a conference keynote the next.

Most of all, founders need the mental fortitude to risk failure and ridicule and to keep pushing ahead despite the inevitable dead ends and near-death moments they’ll hit on the journey.

Many would-be founders look at this list and are so intimidated that they never build up the nerve to get started. Or if they do get a startup off the ground, they quit too early, losing their confidence as everything takes longer than expected and as they hit constant rejection from customers, recruits, and investors.

Arguably, this serves a valuable weeding-out function. Founders wracked with self-doubt shouldn’t start a startup, and those who do should know the challenges they have to overcome.

But founders should make decisions based on reality, and the reality is that even the most successful founding teams struggle with not having enough money, skills, network, or reputation. The best ones focus on what they do have and leverage those things to go out and get the rest.

Ready, set, start

Imagine a reality TV show that locked you in an escape room and awarded you a million dollars if you could find your way out within an hour. When the clock started ticking, you’d inventory everything you see. You might see a map on the wall and a set of colored wooden blocks on the table. You’d draw on your experience from other escape rooms you’ve solved. You’d remind yourself that you have brains, persistence, and a zen-like capacity to stay calm. You wouldn’t waste time thinking about the long list of things you don’t have (yes, a chainsaw would be handy). You’d focus on what you *do* have. The blocks would spell out the location of a key. The key would open a cabinet, and so on. You’d keep following clues until you saw daylight.

Startups require a similar inventory. You have the experiences and motivations that led you to start this startup. You have the skills you’ve obtained from previous jobs and school. You have the Internet, with endless books, blogs, and videos to help you learn the skills you need. You have your professional networks, plus LinkedIn and Twitter to connect you to the people you want to reach. It won’t be easy, but founders have done more with less.

So how do you leverage what you have to start where you are?

Don’t get hung up on credentials

You may have been accepted to a university because your grades and activities appealed to an admissions officer. You may have gotten a job because a hiring manager liked your resume. A boss may have promoted you because you worked on the right projects. In each case, you were rewarded for your credentials.

But credentials are only proxies that signal that you can do a job. In a startup, you don’t get rewarded for signaling. You get rewarded by actually doing that job. And you don’t get rewarded for things you did in the past or penalized for things you didn’t. You only get rewarded for what you produce right now.

If you do have a great resume, leverage it. It will help you get started faster, especially in an early round of financing where some investors will care about your background. But don’t expect it to sustain you for long. Customers don’t care where you went to school or that you were the captain of the soccer team. You are either solving an important problem for them, or you aren't.

And if you don’t have a great resume, don’t let it hold you back. Plenty of great companies were started by founders who could never have gotten a job at Microsoft or McKinsey. Many didn’t have backgrounds in the industries they were disrupting.1 Some didn’t even go to college. They put their focus where you should: the work itself. You can either do it, or you can’t.

Learn from other startups

Startup origin stories can be a source of information and inspiration, and you should take some time to learn from them. But be careful to take away the right lessons.

These stories skew toward the top 0.1% of startups — the Ubers, Amazons, and Snowflakes. These companies and their founders are such outliers that their lessons might not apply to you and might be unrealistic, much like comparing yourself to Messi or Marta would make you wonder if you should even bother kicking a soccer ball.

And founding stories are often sanitized — they describe the founders as oracles who saw the future and bravely charted a course to make that future come true. This almost never happened. Almost all companies are shitshows in the early days, taking a somewhat random walk to success. Steve Jobs dropped out of college and went weeks without bathing. Mark Zuckerberg was awkward, a terrible public speaker, started Facebook as a Florida LLC, and considered selling several times. Slack was a failed gaming company that made a last-minute pivot to a completely unrelated idea.

Find founding stories from both successful and failed startups. Seek out stories told by the founders themselves, not puff pieces filtered through PR agencies and reporters. Yes, you’ll find stories from founders with Stanford MBAs who raised their seed round from their parents’ wealthy friends, but you’ll also find success stories from founders with little money, no fancy schools, and minimal connections, many of them immigrants. For many, it took years of work with low pay and many pivots and false starts before they found traction.

Learn enough to be dangerous

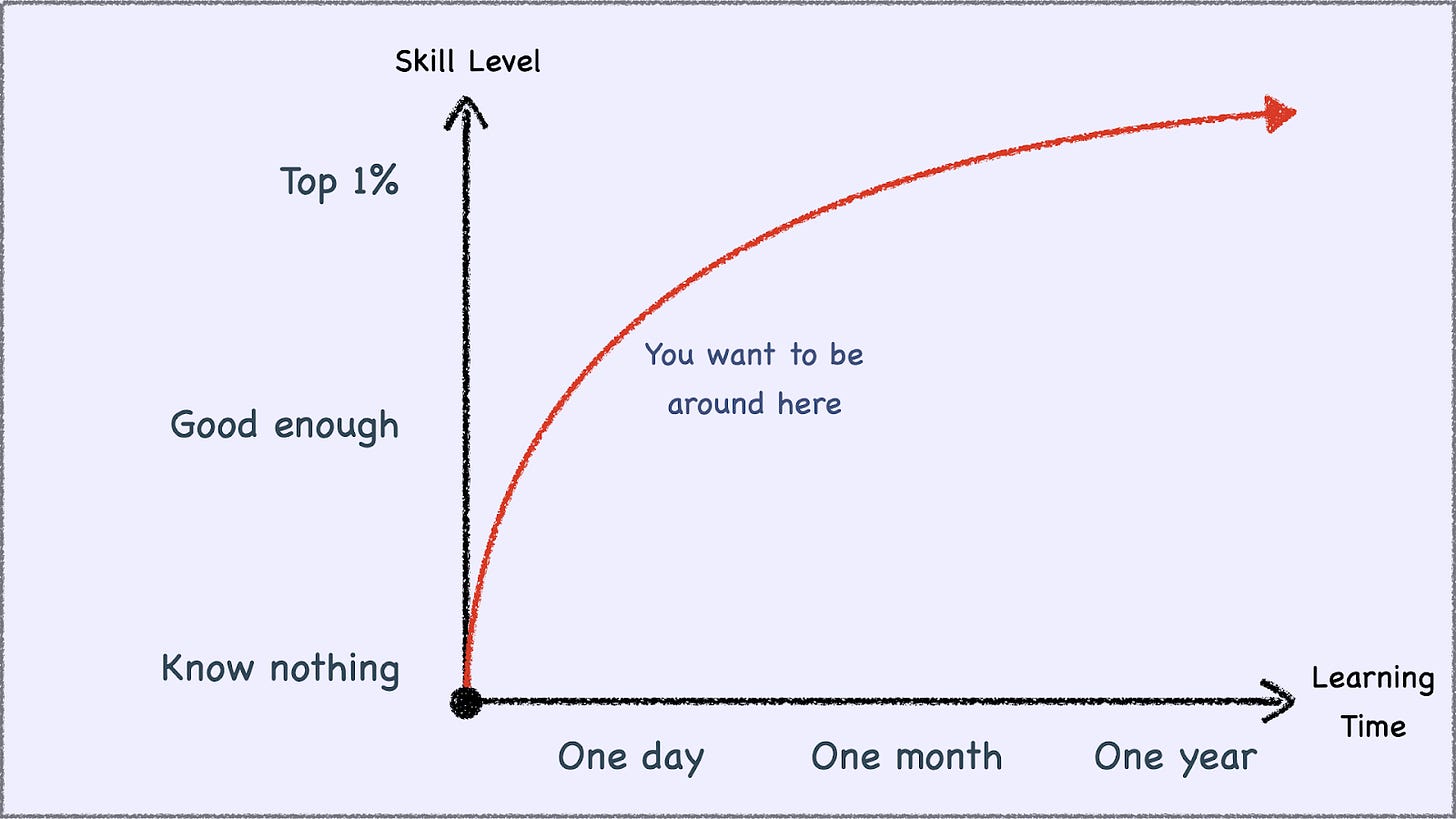

Think of a skill you need to learn, like designing a user interface using Figma, running a social ad campaign, or putting together a financial plan. How long would it take you to become one of the best in the world at one of those things? Years, maybe.

But you don’t need to be the best in the world. You just need to be good enough to muddle through a specific task, and you can probably learn the bare minimum much faster than you think.

What would happen if you spent 10–20 hours focusing on a skill you need—not just flipping through a manual, but “deliberate practice”2 where you work intensely with lots of drills and feedback? You wouldn’t become an expert, but you might know 50% of what an expert would know, which is probably all you need, at least to solve whatever problem is in front of you.

No, you can’t be the best at everything, but you certainly can spend next weekend working through GPT-4 tutorials on YouTube instead of watching football games.

Combine your powers

As you bring a set of skills into your startup and start developing more, you and your co-founders build up a portfolio of skills you can fine-tune to match what your business needs. You might not be the best in the world at any one of those skills, but you can be one of the best at the combination of skills relevant to your startup.

Suppose you know your market well and have learned some basics on how to demo and sell a product. The Venn diagram of those skills might make you one of the best in the world at pitching this particular product to these particular customers:

Maybe you don’t have a Harvard MBA or Bain on your resume, but for *this* company, *this* product, and this* customer meeting, you’d run circles around someone who did. This is why founders are often the best salespeople for their products, even when they think they “suck at sales.” They know more about it, have more passion for it, and get more practice pitching it than anyone else.

Solve the problem right in front of you

You and your team may not have the money and talent to build a huge company, at least not yet, but you aren’t a huge company. Your job at the moment is to get through the next set of milestones, which could be reaching product/market fit, getting your first five customers, or raising a round of funding. Focus just on what it takes to get that done.

Once you graduate to the next phase, you can level up. You’ll have more experience and confidence to bolster you, more customers to learn from, and might be able to add funding to add new people who have some of the skills you lack.

This perspective gives you permission to “Do Things that Don’t Scale”3 and solve the problems that are right in front of you. It also reduces the number of excuses not to do that.

Don’t be intimated by networking

If you are like many founders, especially those who are younger and come from technical backgrounds, you might not see yourself as much of a networker. You are probably better than you think, though.

Social networks, especially LinkedIn and Twitter, make it easy to reach out to your existing network and grow it. If you approach people respectfully, tell them what your startup is doing, show enthusiasm, and make a clear request, you’ll be surprised how many people will respond. Just drop the breathless marketing jargon about your “breakthrough” and “innovative” product that will doom your message to spam folder purgatory.

In-person events also still have their place. Even if you are on the introverted side, it’s not that hard to walk into a room of people with whom you have a lot in common, like other founders or prospects in your market, and connect with them. You don’t need to be magnetic and charismatic. Just let your enthusiasm for your startup show, be curious about who they are and what challenges they face, and soon you’ll be making valuable connections.

Use your founder cheat code

The day you start your startup, you are issued a valuable asset, much like starting a video game with a cache of weapons: the founder cheat code.

Are you worried about getting prospects to return your calls? Tell them you are the founder of the company and would value a few minutes of their time. An executive who ignores a dozen messages a day from sales reps will often respond to a message from a founder.

Are you worried about building a team? Many recruits will be thrilled to meet a founder and hear how you started your startup, your vision, and how they can play a role. They might even want to start their own startup someday and welcome the chance to learn from you.

Most of all, as a founder, you know your business better than anyone else and have more passion to see it succeed than the incumbents you’ll compete against. That passion will help you power through the challenges you’ll face, which we’ll cover next in Know What You Believe.

If you have feedback or suggestions for future posts, please comment or contact us at uninvent@substack.com.

Patrick and John Collison started Stripe at ages 19 and 21, never having worked in financial services. Blake Scholl, the founder of the supersonic airplane company Boom, never worked in the aerospace industry and got started by taking Khan Academy physics courses. Elon Musk learned about building rockets for SpaceX by reading textbooks.

The kind of learning I’m describing doesn’t mean flipping through manuals for a few hours. It means focusing intensely, doing hands-on exercises, seeking feedback, and making corrections. It means what Malcolm Gladwell described as Deliberate Practice, although for more like 10 hours, not 10,000. This TED Talk also does a great job covering this concept.

Paul Graham’s Do Things that Don’t Scale is another must-read, especially for newer founders. It both relieves you from the burden of worrying about scale early on, but it also removes excuses to not jump in and solve the problems you have today. No, you can’t call 10,000 customers, but you have no excuse not to call 100.

Inspiring and thoughtful. Thank you!

good stuff